Beautiful And Haunting Pictures Of Indigenous Americans In Traditional Masks and Dress

When you think of Native Americans, you may have a singular image in mind. It’s not surprising, considering that the indigenous people of the Americas—and their cultures—have been subject to systematic erasure over the last 500 years. Through disease, gunpowder, or “assimilation schools,” a rich diversity of history, tradition, and artistry has been all but swept away.

If it hadn’t been for Edward Curtis, a photographer born in 1868, these traces of a grand civilization would have been entirely lost to time. These masks are beautiful to behold—but they also carry great spiritual and cultural significance. Appreciate these treasures for what they are—a thin fraction of what has been lost.

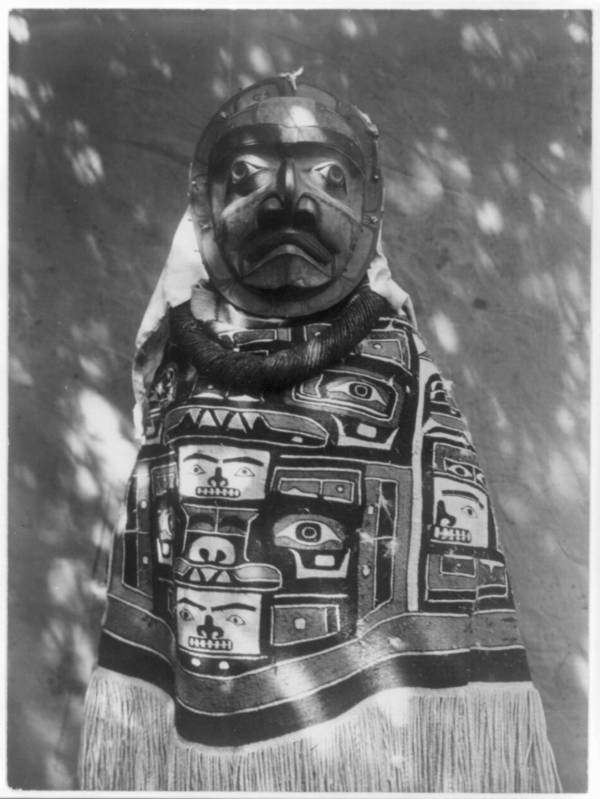

Hamatsa Throw And Mask

This photograph depicts a woman in a Chilkat blanket, beautifully ordained with colorful artwork of faces—eyes, mouths, smiles—while wearing a Hamatsa neck ring. The Hamatsa were a secretive group with a fascinating history too wide and deep to penetrate here.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

The mask she wears depicts a deceased family member. Masks were often integral to Native American storytelling and spirituality. The mask itself is intricate and bold. The features of the mask and the blanket have a surreal quality that goes beyond words.

The Headwear Of A Navajo Man

This portrait is otherworldly. Behind this evocative Navajo dress is a man. Feathers adorn a mass of hair that resembles roots. He wears a wreath of spruce branches around his neck. The pale face resembles that of an owl or bird of prey.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

He sits monk-like for the photographer to work his device. While taking these pictures over the course of his career, Curtis knew that his work would likely someday become all that remained of many of the indigenous people.

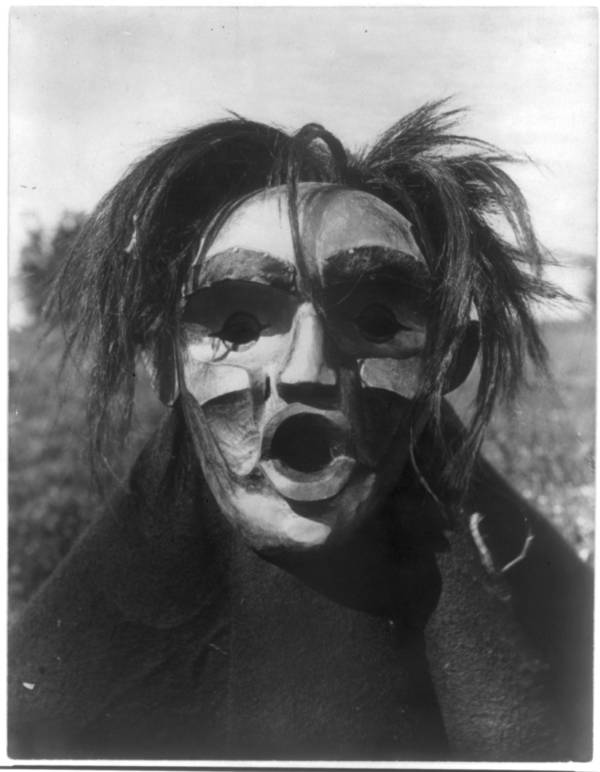

Tsunukwalahl

This is the mask of Tsunukwalahl taken in the year 1914. Little has been recorded about this figure, besides the fact that he was a mythical being and that his likeness was used during the Winter Dance. The more you look into this mask’s eyes, the more familiar they seem.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

His face seems to have been frozen in a great bellow, or perhaps surprise. It may simply be the expression of the spirit; simply put, it is not for us to say. This mask has striking features that are both hard and soft simultaneously.

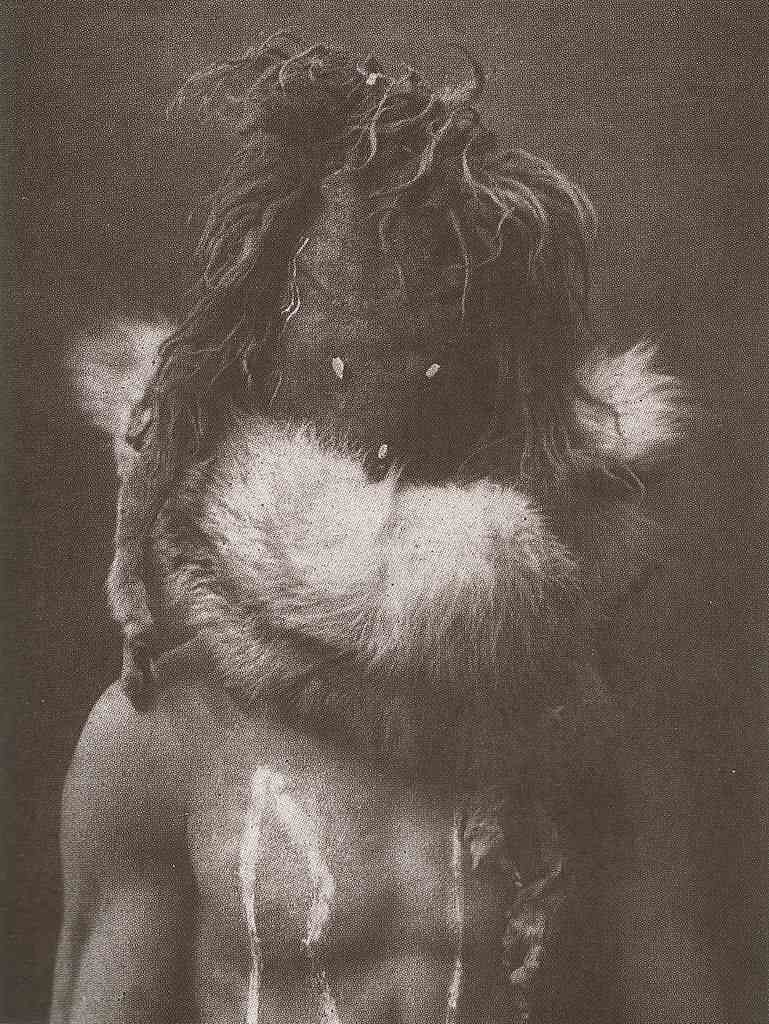

Dangerous Hami

This full-body fur dress represents Hami, which to the Koskimo peoples meant “dangerous thing.” With those giant gloves and head, it’s easy to get a sense of what that means. Curtis took this photograph during the Numhlim ceremonies in 1914, the year before his wife divorced him for his documentary pursuits.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

It looks like those enormous hands could have been used for violence or calamity. They really speak to the phrase “heavy-handed.” The mask, with its deep ridges and exaggerated features, really transforms its wearer into a colorful character.

An Avatar Of Disorder

Many of these photographs were taken during the Winter Dance ceremony. Curtis seems to have been lucky enough to witness a great many of these beautiful and haunting masks in action, all in one place.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

This image depicts a Nuhlimahla ceremonial mask wearer. Characters such as these were used to embody foolishness and idiocy—they craved disorder, grime, and madness. These masks carry striking expressions that seem alive though the images are still.

The Trickster God Of Rain

Many characters in Indigenous American culture are larger than life and often represent wildness and mischief. This Navajo man is outfitted in hemlock and a mask relating to Tonenili, which means “Sprinkler of Water.”

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

This picture was taken in 1905. The background has an otherworldly quality about it which helps transform the hemlock-garbed figure into something genuinely mythical—like a human being sprouting from a bush or tree.

The Sisiutl

One of the central figures in the Winter Dance, this hemlock adorned figure dons a mask with two diverging sea serpents. The Sisiutl is seen as a mediator between physical and supernatural realities, an ability that shamans are commonly believed to share.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

The interpretations of this character are as varied as the cultures that depict it. Some cultures portray it with three heads, some with two. Usually, the heads are horned. Some cultures believed that killing the Sisiutl would deliver healing magics; others believed its blood would make a warrior invulnerable.

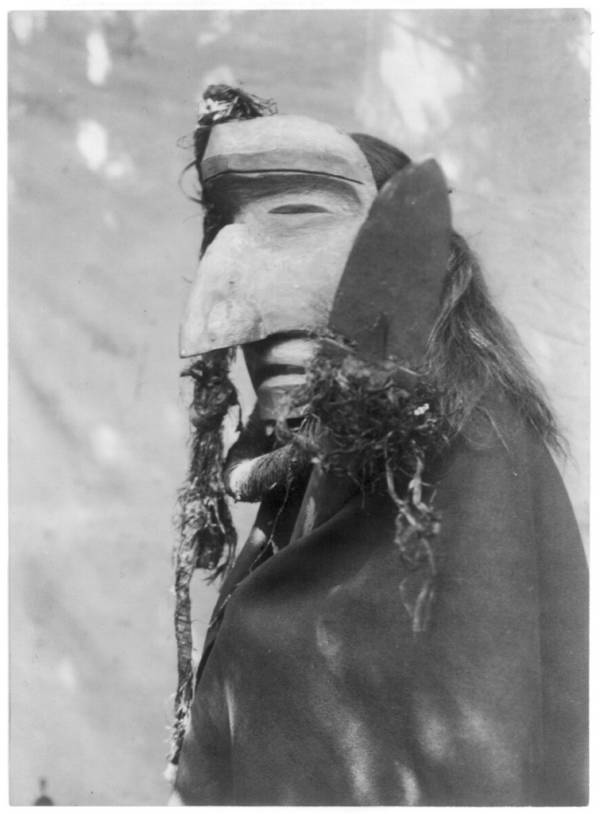

The Hunter

This frightening face has an interesting story. It is used during the four-day ceremonial Winter Dance to depict the hunter who slays a giant man-eating octopus! Its grizzled look and gnashing teeth display a fierce determination.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

These masks were not donned as a disguise to hide the wearer’s identity. They were used to celebrate both tradition and culture as well as the aspects of the wearer, the latter being hidden deep within the individual. The mask is used to help put that aspect front and center.

Nunivak Mask

In some cultures, the masks themselves were considered living—yet intangible—beings with their own will and personalities. This is a picture of a man in a Nunivak mask, taken by Curtis as late as 1929. A calmness emanates from this face, carved as it is with sensual, smooth angles.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

It’s a tragedy that the treasures that these peoples held so dearly were targeted for destruction over the last few centuries. The US and Canadian governments sought to erase the identity of the remaining few after tens of millions had been killed since the arrival of the European settlers.

Full Ceremonial Dress And Paint

In this picture, a Navajo man stands with his bow wearing furs and body paint. What’s striking about each of these pictures is just how different each dress and mask is. There’s such a great variety in each persona—in each spirit—each dancer attempts to embody.

Edward Curtis/Library of Congress

The photographer Edward Curis worked tirelessly throughout his career to document these beautiful ceremonial dresses and masks at the cost of his reputation and even marriage. He thought it incredibly important to create memories of these people before they were swept away by violence—and we have to agree.

Kachinas: Spirits from Ancient Pueblo

This image, taken in 1925, represents the revered Kachinas of Native American cultures. Kachinas are said to be more than just a spiritual entity. In the Pueblo traditions is where kachina rites come alive.

Source: Pinterest

It is a sacred practice of the Hopi, Zuni, and numerous Pueblo communities in New Mexico. The men from the Pueblo tribe usually perform symbolic dances while dressed in Kachina regalia to symbolize the Kachina spirits.

The Spirit Of The Buffalo Dance

The Buffalo Dance is a traditional ceremony that features a display that is much more than a mere performance. The picture, taken in 1904, portrays two dancers adorned in regalia that embody the spirit of the buffalo.

Source: Getty Images

During their ceremonies, their movements mirror the strength and grace of these majestic creatures. This is one of the deeply-rooted traditions passed down through generations to keep the spirit of the land alive.

Haschezhini-Navaho

This portrait, captured in 1905, also forms part of Edward S. Curtis’s collection. It depicts a Native American man personifying the Black God, who is called Haschezhini.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The Black God is distinguished by markings that depict the crescent moon and also a full moon, as well as the Pleiades gracing his temple. It. He is said to embody the supernatural forces that shape the universe through the use of fire.

Hamasilahl, The Wasp-Embodiment

The captivating image serves as a visual representation of the true primitive life of the Qagyuhl tribe. The striking portrait by Curtis was taken in 1914. The name Hamasilahl translates to “Wasp-Embodiment,” which resonates with the appearance of the attire of the individual wearing it.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

The sophistication of their masks and costumes really set the Qagyuhl apart from other tribes. This image tells a tale of the tribe’s cultural heritage.

The Mystical Zahadozha

The mystical Zahadozha is another aspect of the Navajo folklore captured by Curtis. The Zahadozha is a water spirit referred to as “fringe mouth.” It derives this name from the unique markings on its mouth.

Source: Getty Images

According to Navajo tradition, this water spirit holds a role as a protector, and those who are rescued by this spirit express their appreciation. The Navajo mask details an intricate design of black and white.