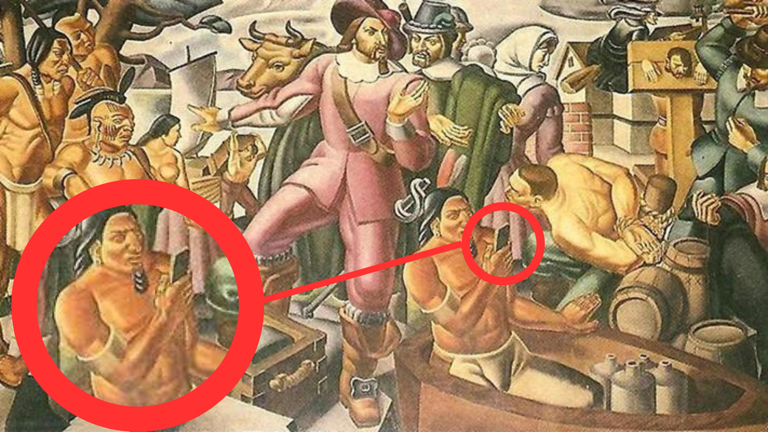

Umberto Romano created the painting “Mr. Pynchon And The Settling Of Springfield” in 1937, and it remains unchanged to this day. The artwork depicts the 17th-century negotiation between English settler William Pynchon and the indigenous people of Springfield, Massachusetts.

The painting was crafted during the New Deal era, nearly seventy years before the iPhone came into existence. It loosely portrays a real-life event that occurred in the 1630s at the village of Agawam, present-day Massachusetts, involving the Pocumtuc and Nipmuc tribes and English settlers, long before the discovery of electricity.

<iframe width=”100%” height=”100%” frameborder=”0″ allowfullscreen=”true” src=”https://www.youtube.com/embed/DffQS-F17_c?rel=0″></iframe>

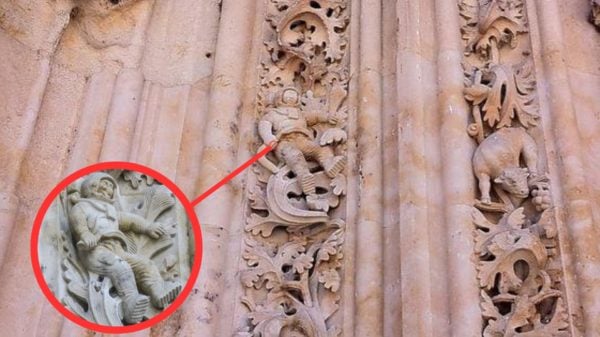

At the bottom right of the piece, there is a visible depiction of a man holding a device that resembles a smartphone near his face. The way he is holding the object is similar to how individuals typically hold their smartphones while browsing social media, with their fingers positioned behind the device and their thumb in front for tapping on the screen.

The Springfield Commonwealth of Massachusetts State Office Building is currently displaying a series of murals, one of which was created by the late Italian artist Romano. Regrettably, as Romano passed away in 1982, well before the advent of the iPhone, it is not possible to consult him regarding the item held by the Native American depicted in the mural.

As per the information available on the VICE website, writer and historian Daniel Crown was the first to point out the figure in the artwork holding an object that resembles a smartphone. However, Crown clarified in his essay on William Pynchon that despite the apparent similarity to an iPhone, the object held by the figure is likely something else.

Crown commented, “To put it into the kindest words possible, Romano’s self-proclaimed ‘abstract’ style was deliberately unclear.”

During the creation of the mural, there was a prevailing fascination among Americans with the concept of the ‘noble savage.’ It can be inferred that Romano aimed to depict the integration of modernity into a technologically deprived community, entranced by the new and shiny objects brought by Pynchon, in a simplistic manner, as the mural centers on the founding of Springfield.

Daniel Crown’s educated speculation is that the object held by the figure in the mural is probably a small mirror, rather than an item brought from the future by time travelers. Some other specialists have put forth a theory that it might be a roughly illustrated knife or blade.

What we do know, however, is that in the 1600s, Europeans introduced reflective objects to the Indigenous population. As Dr. Jessica R. Metcalfe, an authority on Indigenous fashion, design, and art, notes in a 2011 blog post, many Native tribes integrated mirrors into their aesthetic and cultural practices.

Metcalfe, a member of the North Dakotan Turtle Mountain Chippewa, cites Edwin L. Wade’s book “The Arts of the Native American,” a 1986 work in which the Native art specialist reflects on the varying uses of mirrors among Indigenous peoples and European settlers during that period.